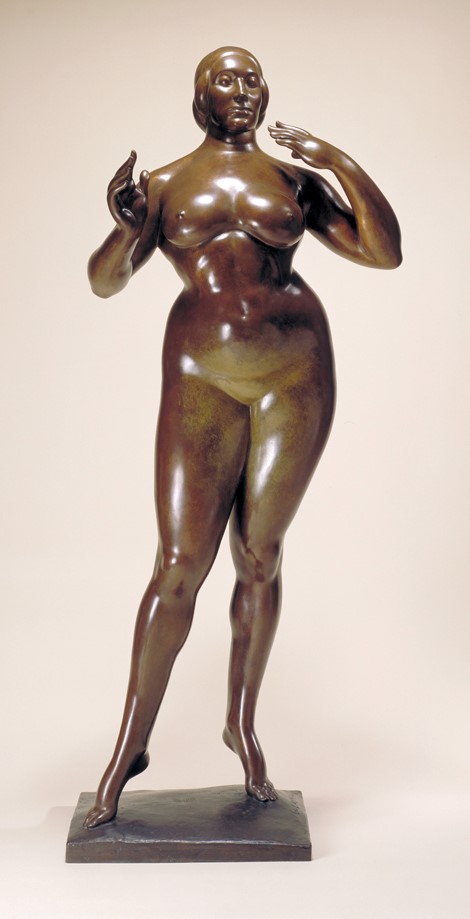

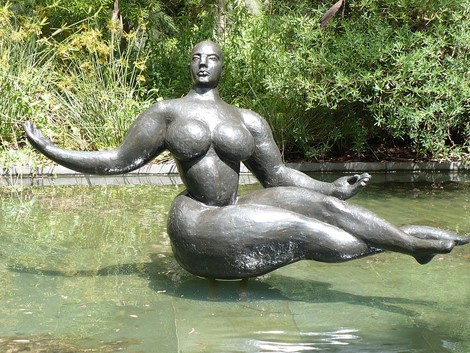

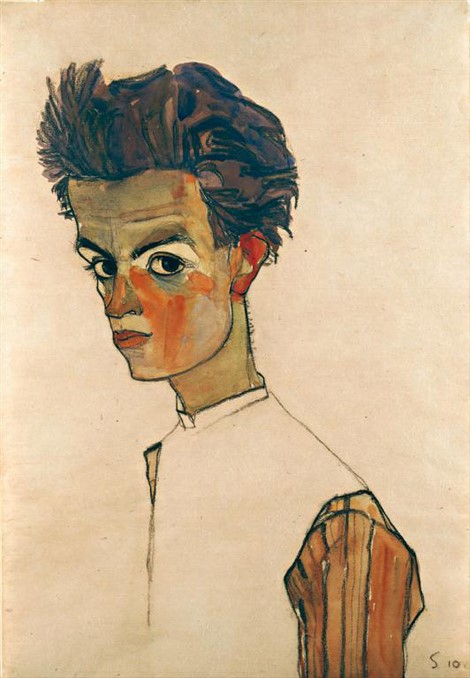

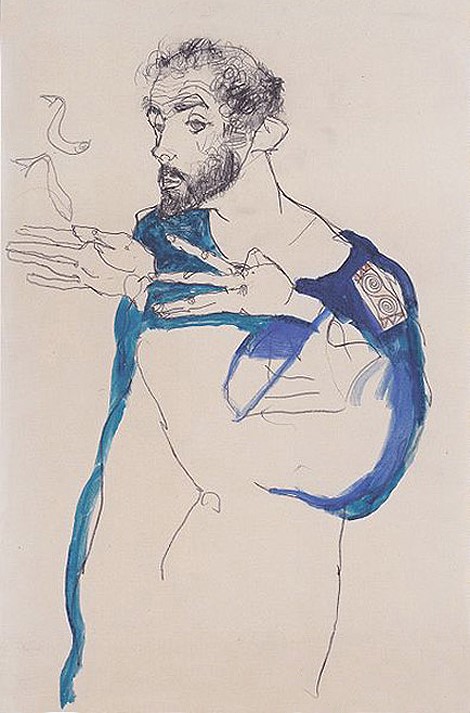

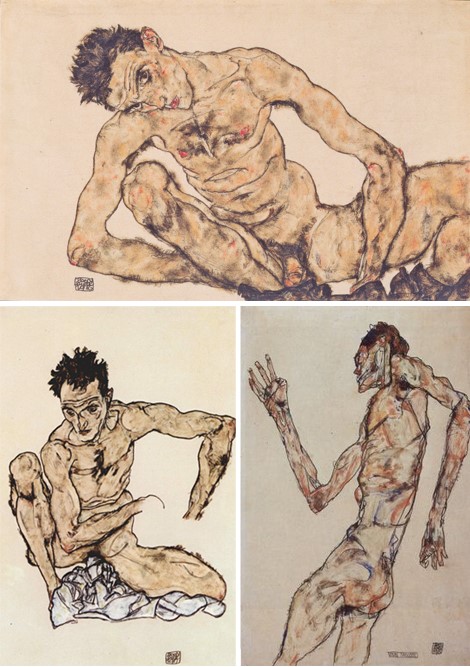

Right from its beginnings, Modern Art seems to have had a bad case of anorexia. Perhaps the artists involved felt an emaciated body better conveyed the emotional tenor of contemporary life.

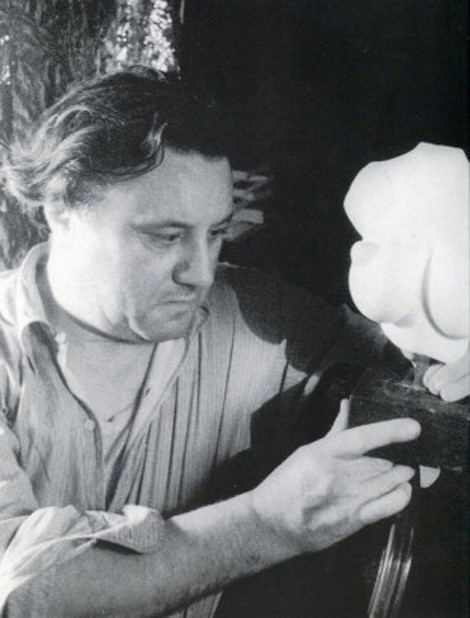

Not so for Parisian-born sculptor Gaston Lachaise (1882-1935). After having successfully finished his art education at the Écoles des Beaux Arts, the young artist was staring absently across the Seine when his attention was seized by a woman strolling, along with so many others, through the gardens lining the Champs-Élysées. He wrote later that he knew at that moment he had found his muse. He followed her, begged her to allow him to draw her portrait. A love affair that would last a lifetime had begun. The figure Lachaise had viewed from afar turned out to be an American woman of French Canadian origins. Her name was Isabel Dutaud Nagle. There were more than a few obstacles to her fulfilling the roll of the artist’s muse. Besides being a total stranger, she was ten years his senior and married. She was on vacation, soon to return home. And home was Boston.

However, whether through persistence or charm, or both, the young artist’s love was returned, so none of these impediments seemed insurmountable to the smitten Lachaise. To earn passage to Mrs. Nagel’s home city, Lachaise took a job with Rene Lalique designing Art Nouveau jewelry. Once in America, the penniless but skilled artist became an assistant to a sculptor of war monuments. He learned English. He absorbed the idiom of an emerging American Modernism. But mostly he revelled in the fulsome beauty of his beloved ‘Belle’. He wrote, “Through her, the splendour of life was uncovered for me”. Soon an inconvenient husband was dispensed with and conservative Boston was abandoned for woodland frolics in Maine.

Later came marriage, New York and fame. In New York, Lachaise refined the vision of ‘eternity and serenity’ his partnership with Isabel Dutaud Nagel had brought him. By enlivening the cool sleekness of Art Deco with the robustness of a particular living lady, Lachaise’s art caught the attention of American critics and delighted the public.

In 1935 the Museum of Modern Art honoured Lachaise with its first retrospective awarded to a living sculptor. By this time the former Frenchman had come to be seen as one of the chief innovators of American Modernism. And all this without producing a single undernourished waif in bronze or plaster.

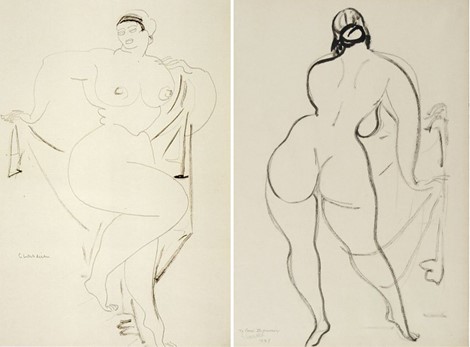

For this Wednesday’s extended session of the Open Studio, our model will be taking poses inspired by the artwork of Gaston Lachaise. The evening will start at 7pm and run until 10pm. We will have a series of gestures in the first hour, two medium length poses in hour two and a single long pose in the final hour. As always, you are welcome to attend for whatever combination of times suits your schedule. The fee for two hours is $10; for three $15. Hope to see you there!

~ Ken Nutt, Open Studio